This is the greatest piece of automotive journalism ever written. Bar none. Denis 'Jenks' Jenkinson's Motor Sport Magazine account of Sir Stirling Moss' epic, record-breaking win in the 1955 Mille Miglia. Jenks was Moss' navigator that day, and his story is simply a riveting read. And yes, I have read David E. Davis' legendary "Turn Your Hymnals to 2002". That is Number Two, in my book. I know that is heretical, but it is true: THIS is Numero Uno! ;) https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/june-1955/14/moss-mille-miglia

With Moss in the Mille Miglia

On May 1st motor-racing history was made, for Stirling Moss won the 1,000-mile Mile Miglia, the first time in twenty-two years that this has been achieved by a British driver, and I had the very great privilege of sitting beside him throughout this epic drive.

But let us go back to the beginning, for this win was not a fluke on the spur of the moment, it was the result of weeks, even months, of preparation and planning. My enthusiasm for the Mille Miglia race goes back many years, among the reasons being the fact that it is permissible to carry a passenger, for this event is for all types of road-going cars, from family saloons to Grand Prix-type racing/sports cars, and when I had my first taste of the lure of the Mille Miglia as a competitor last year, with Abecassis in the H.W.M., I soon set about making plans for the 1955 event.

Regular Motor Sport readers will remember that last year I enthused over a little private dice that Moss gave me in a Maserati, and at the time I mentioned to him my desire to run in the Mille Miglia again. Then in September, whilst in discussion with the American driver John Fitch, we came to the decision that the only way a non-Italian could win the Mille Miglia was by applying science. At the time he was hoping to be in the official Mercédès-Benz team for the event, and we had long talks about ways in which the driver could use a passenger as a mechanical brain, to remove the responsibility of learning the circuit. When it is realised that the race is over 1,000 miles of ordinary, unprepared Italian road, the only concession to racing being that all traffic is removed from the roads for the duration of the race, and the way through towns is lined with straw bales, it will be appreciated that the task of one man learning every corner, every swerve, gradient, hummock, brow and level-crossing is nigh impossible. Even the top Italian drivers, such as Taruffi, Maglioli, Castellotti, etc., only know sections of the route perfectly, and all the time they must concentrate on remembering what lies round the next corner, or over the next brow.

During the last winter, as is well known, Moss joined the Mercedes-Benz team and the firm decided that it would not be possible for Fitch to drive for them in the Mille Miglia, though he would be in the team for Le Mans, so all our plans looked like being of no avail. Then, just before Christmas, a telephone call from Moss invited me to be his passenger in the Mille Miglia in a Mercédès-Benz 300SLR, an invitation which I promptly accepted, John Fitch having sportingly agreed that it would be a good thing for me to try out our plans for beating the Italians with Moss as driver.

When I met Moss early in the new year to discuss the event I already had some definite plan of action. Over lunch it transpired that he had very similar plans, of using the passenger as a second brain to look after navigation, and when we pooled our accumulated knowledge and ideas a great deal of ground work was covered quickly. From four previous Mille Miglia races with Jaguars Moss had gathered together a good quantity of notes, about bumpy level-crossings, blind hill-brows, dangerous corners and so on, and as I knew certain sections of the course intimately, all this knowledge put down on paper amounted to about 25 per cent of the circuit.

Early in February Mercédès-Benz were ready to start practising, the first outing being in the nature of a test for the prototype 300SLR, and a description of the two laps we completed, including having an accident in which the car was smashed, appeared in the March Motor Sport. While doing this testing I made copious notes, some of them rather like Chinese due to trying to write at 150 m.p.h., but when we stopped for lunch, or for the night, we spent the whole time discussing the roads we had covered and transcribing my notes. The things we concentrated on were places where we might break the car, such as very bumpy railway-crossings, sudden dips in the road, bad surfaces, tramlines and so on. Then we logged all the difficult corners, grading them as “saucy ones”, “dodgy ones” and “very dangerous ones”, having a hand sign to indicate each type. Then we logged slippery surfaces, using another hand sign, and as we went along Moss indicated his interpretation of the conditions, while I pin-pointed the place by a kilometre stone, plus or minus. Our task was eased greatly by the fact that there is a stone at every kilometre on Italian roads, and they are numbered in huge black figures, facing oncoming traffic.

Stirling Moss pictured next to his Mercedes 300SLR during testing at Hockenheim

Daimler

In addition to all the points round the course where a mistake might mean an accident, and there are hundreds of them, we also logged all the long straights and everywhere that we could travel at maximum speed even though visibility was restricted, and again there were dozens of such points. Throughout all this preliminary work Moss impressed upon me at every possible moment the importance of not making any mistakes, such as indicating a brow to be flat-out when in reality it was followed by a tight left-hand bend. I told him he need not worry, as any accident he might have was going to involve me as well, as I was going to be by his side until the race was finished. After our first practice session we sorted out all our notes and had them typed out into some semblance of order, and before leaving England again I spent hours with a friend, checking and cross-checking, going over the whole list many times, finally being 100 per cent. certain that there were no mistakes.

On our second visit to Italy for more laps of the circuit, we got down to fine details, grading some corners as less severe and others as much more so, especially as now we knew the way on paper it meant that we arrived at many points much faster than previously when reconnoitring the route. On another lap I went the whole way picking out really detailed landmarks that I would be able to see no matter what the conditions, whether we had the sun in our eyes or it was pouring with rain, and for this work we found Moss’ Mercédès-Benz 220A saloon most useful as it would cruise at an easy 85 m.p.h. and at the same time we could discuss any details.

“Moss said he’d ease it back to 160 m.p.h. for, though that 10 m.p.h. would make no difference to the resulting crash if I had made a mistake, it comforted him psychologically!”

Our whole plan was now nearing completion, we had seventeen pages of notes, and Moss had sufficient confidence in me to take blind brows at 90-100 m.p.h., believing me when I said the road went straight on; though he freely admitted that he was not sure whether he would do the same thing at 170 m.p.h. in the race, no matter how confident I was. He said he’d probably ease it back to 160 m.p.h. for, though that 10 m.p.h. would make no difference to the resulting crash if I had made a mistake, it comforted him psychologically! Throughout all this training we carefully kept a log of our running time and average speeds, and some of them were positively indecent, and certainly not for publication, but the object was to find out which parts of the 1,000 miles dropped the overall average and where we could make up time, and our various averages in the 220A, the 300SL and the 300SLR gave us an extremely interesting working knowledge of how the Mille Miglia might be won or lost.

Our second practice period ended in another accident and this time a smashed 300SL coupé, for Italian army lorries turn across your bows without warning just as English ones do. Rather crestfallen, we anticipated the rage of team-chief Neubauer when we reported this second crash, but his only worry was that we were not personally damaged; the crashed car was of no importance; these things happened to everyone and anyway their only interest was to win the Mlle Miglia, regardless of cost.

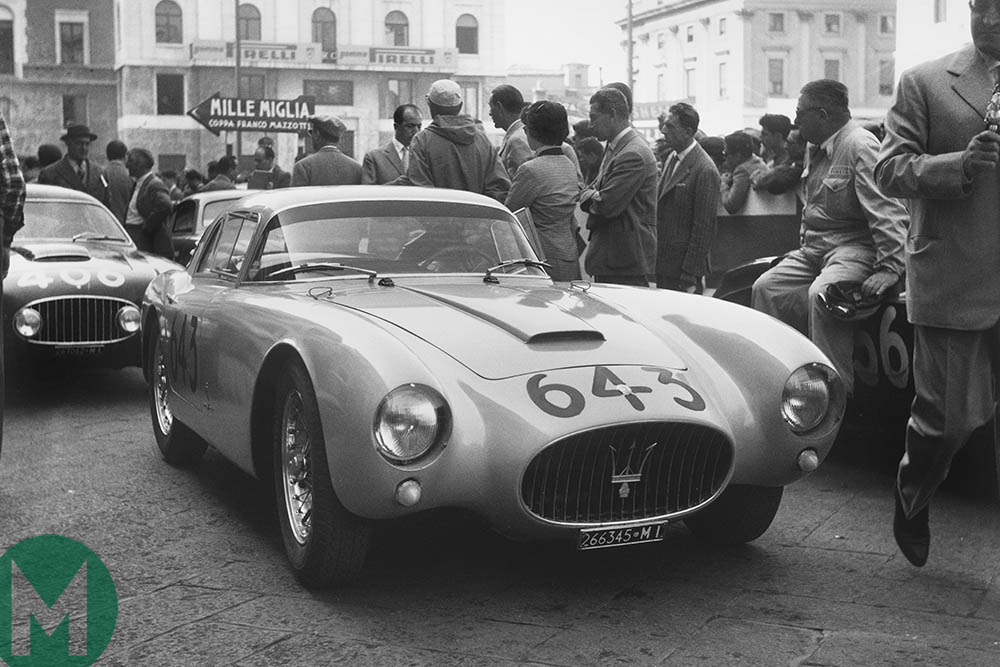

Motor Sport correspondent Denis Jenkinson and Stirling Moss prepare for the start of 1955 Mille Miglia

Daimler

Leaving Italy for another brief respite, we both worried-out every detail we could think about, from every aspect, the car, the route, our hand signals — for we could not converse in the 300SLR — any emergencies that might arise, anywhere we could save seconds, details of our own personal comfort which would avoid fatigue, and so on. We lived and breathed Mille Miglia day in and day out, leaving no idea untried. The joy of all this was that Daimler-Benz were doing exactly the same things on the mechanical side, supervised by engineers Uhlenhaut, Kosteletzky and Werner, while the racing department were working unceasingly and Neubauer was worrying-out every detail of the race-organisation in Italy. We were putting all our efforts into this race, knowing that they were negligible in comparison with those of the factory.

After Easter we went out to Brescia for our third and final practising session, the technical department, with Kling and Herrmann, having already made an extra one. During their practice period they had thrashed the prototype car up and down the section from Rome to Florence, for this part of the route was the hardest. There are few straights, but all the time the car is averaging nearly 100 m.p.h., the chassis being subjected to strains from every possible angle, and as the 58-gallon petrol tank would be full when leaving Rome, this part of the route would be the most likely on which a breakdown would occur.

A week before the event we went to Stuttgart to try out the actual car we were using in the race, and several laps of the fast Hockenheim circuit convinced us that we had a truly magnificent 3-litre sports car under us, the eight-cylinder fuel-injection engine giving well over 290 b.h.p. on normal pump petrol, and the car geared to give a maximum of 170 m.p.h. at the peak revolutions of 7,500 r.p.m., though we were given no ultimate limit, should the car wind itself over this downhill. On this SLR the seats were made to measure for us, being cut-and-shut just like a tailor would make a suit, while every detail in the cockpit received our personal attention, and anything was altered to our desire without question. When we finally left the racing department at 5 p.m. on Tuesday, April 26th, we had the pleasant feeling that we had just left an organisation that knew no limit to the trouble they would go to in order that we might start the Mille Miglia with everything on our side.

Motor Sport correspondent Denis Jenkinson and Stirling Moss before the start of the race

Daimler

Next day we flew to Brescia and when we went round to the garage in the evening the cars were already there, having been driven down in the fast racing lorries overnight. We were now satisfied with almost everything we could think about; we had practised wheel-changing over and over again, in case we had tyre trouble, and I would add that we impressed the Mercédès-Benz mechanics by changing a rear wheel in 1 min. 25 sec. from stopping the car to starting off again, including getting the tools and spare wheel out of the boot and putting everything back again. We had practised fitting the temporary aluminium aero-screens that went in front of the Perspex screen should it be broken by a stone—Mercédès-Benz engineers remembering how Hermann Lang was nearly suffocated at 170 m.p.h. at Donington Park in 1938 when his windscreen was broken. We had tried changing plugs; we had studied the details of the pipes of the fuel-injection, the petrol pumps, various important parts of the wiring system, how the bonnet catches functioned; we were given spare ignition keys, shown where numerous small spares were stowed should we stop by the roadside with minor trouble; and by the end of the week we felt extremely confident that we could give of our best in this toughest of motor races, lasting for more than 10 hours over every known road condition, over mountains and through cities, for 1,000 miles.

On the Friday before the race we did a final test on the nearby Autostrada, to try-out some windscreen modifications to improve the air-flow along the cockpit sides. Also Moss tried out a new mechanism fitted to the gear-change that would prevent him from changing from second gear to fifth gear. The gear-gate is exposed, with first left-forward, second centre-rear, third centre-forward, fourth right-rear, and fifth right-forward. Being used to four-speed boxes Moss was occasionally going across the gate from second to fifth, and when he told the engineers about this the racing department set to and designed, drew and made an entirely foolproof link mechanism that fitted on the top of the gate that would prevent this. He mentioned this on Tuesday afternoon and on Friday morning the new parts arrived in Brescia and he was trying the mechanism out before lunch — at such speed does a true racing department work.

For the week before the race I had been going to bed extremely early and getting up extremely early, a complete reversal of my normal life, for to suddenly get up at 6 a.m. gives me a feeling of desolation until well past mid-morning. Moss had been employing similar tactics, so that when we went down to the start at 6.30 a.m., on the morning of May 1st we were both feeling ready for anything.

Juan Manuel Fangio prepares to roll off in his Mercedes

Daimler

All the previous week a truly Italian sun had blazed out of the sky every day and reports assured us that race-day would be perfectly dry and hot, so we anticipated race speeds being very high. I had a list of the numbers of all our more serious rivals, as well as many of our friends in slower cars, and also the existing record times to every control point round the course, so that we would have an idea of how we were doing. We had privately calculated on an average of 90 m.p.h. – 2 m.p.h. over the record of Marzotto, providing the car went well and the roads were dry. Mercédès-Benz gave us no orders, leaving the running of the race entirely to each driver, but insisting that the car was brought back to Brescia if humanly possible. Moss and I had made a pact that we would keep the car going as long as was practicable having decided in practice at which point we could have the engine blow-up and still coast in to the finish, and how many kilometres we were prepared to push it to the finish, or to a control. At Ravenna, Pescara, Rome, Florence and Bologna there were Mercédès-Benz pits, complete with all spares, changes of tyres should it start to rain, food, drink and assistance of every sort, for in this race there are no complicated rules about work done on the car or outside assistance; it is a free-for-all event.

“If we didn’t press-on straight away there was a good chance of the dice becoming a little exciting, not to say dangerous”

The enormous entry had started to leave Brescia the previous evening at 9 p.m., while we were sleeping peacefully, the cars leaving at 1-min. intervals, and it was not until 6.55 a.m. on Sunday morning that the first of the over-2,000-c.c. sports cars left. It was this group that held the greatest interest, for among the 34 entries lay the outright winner of this race, though many of the 2-litre Maseratis and smaller Oscas and Porsches could not be overlooked. Starting positions were arranged by ballot beforehand and the more important to us were: Fangio 658, Kling 701, Collins (Aston Martin) 702. Herrmann 704, Maglioli (Ferrari) 705; then there went off a group of slower cars, and Carini (Ferrari) 714, Scotti (Ferrari) 718, Pinzero (Ferrari) 720, and then us at 7.22 a.m. There was no hope of seeing our team-mates, for they left too long before us, as did Maglioli, but we were hoping to catch Carini before the end. Our big worry was not so much those in front, but those behind, for there followed Castellotti (Ferrari 4.4-litre) 723, Sighinolfi (Ferrari 3.7-litre) 724, Paulo Marzotto (Ferrari 3.7-litre) 725, Bordoni (Gordini 3-litre) 726, Perdisa (Maserati 3-litre) 727 and, finally, the most dangerous rival of them all, that master tactician, Taruffi (Ferrari 3.7-litre) 728. With all these works Ferraris behind us we could not hang about in the opening stages, for Castellotti was liable to catch us, and Sighinolfi would probably scrabble past us using the grass banks, he being that sort of driver, and Marzotto would stop at nothing to beat the German cars, so if we didn’t press-on straight away there was a good chance of the dice becoming a little exciting, not to say dangerous, in the opening 200 miles.

Neubauer was ever present at the start, warning Moss to give the car plenty of throttle as he left the starting ramp, for Herrmann had nearly fluffed his take-off; he also assured us that we could take the dip at the bottom of the ramp without worrying about grounding. The mechanics had warmed the engine and they pushed it up onto the starting platform to avoid unnecessary strain on the single-plate clutch, one of the weak points of the 300SLR. The route-card which we had to get stamped at the various controls round the course was securely attached to a board and already fitted in its special holder, the board being attached by a cord to one of my grab-rails, to avoid losing it in the excitement of any emergency. We both settled down in our seats, Moss put his goggles on, I showed him a note at the top of my roller device, warning him not to apply the brakes fiercely on the first corner, for the bi-metal drums needed a gentle application to warm them after standing for two days.

The Moss/Jenkinson Mercedes rolls off at the start

Daimler

Thirty seconds before 7.22 a.m. he started the engine, the side exhaust pipes blowing a cloud of smoke over the starter and Sig. Castegnato and Count Maggi, the two men behind this great event, and then as the flag fell we were off with a surge of acceleration and up to peak revs, in first, second and third gears, weaving our way through the vast crowds lining the sides of the road. Had we not been along this same road three times already in an SLR amid the burly-burly of morning traffic, I should have been thoroughly frightened, but now, with the roads clear ahead of us, I thought Moss could really get down to some uninterrupted motoring. We had the sun shining full in our eyes, which made navigating difficult, but I had written the notes over and over again, and gone over the route in my imagination so many times that I almost knew it by heart, and one of the first signals was to take a gentle S-bend through a village on full throttle in fourth gear, and as Moss did this, being quite unable to see the road for more than 100 yards ahead, I settled down to the job, confident that our scientific method of equalling the Italians’ ability at open-road racing was going to work.

At no time before the race did we ever contemplate getting into the lead, for we fully expected Fangio to set the pace, with Kling determined to win at all costs, so we were out for a third place, and to beat all the Ferraris. Barely 10 miles after the start we saw a red speck in front of us and had soon nipped by on a left-hand curve. It was 720. Pinzero, number 721 being a non-starter. By my right hand was a small grab rail and a horn button; the steering was on the left of the cockpit, by the way, and this button not only blew the horn, but also flashed the lights, so that while I played a fanfare on this Moss placed the car for overtaking other competitors. My direction indications I was giving with my left hand, so what with turning the map roller and feeding Moss with sucking sweets there was never a dull moment. The car was really going well now, and on the straights to Verona we were getting 7,500 in top gear, a speed of 274 k.p.h., or as close to 170 m.p.h. as one could wish to travel. On some of these long straights our navigation system was paying handsomely, for we could keep at 170 m.p.h. over blind brows, even when overtaking slower cars, Moss sure in the knowledge that all he had to do was to concentrate on keeping the car on the road and travelling as fast as possible. This in itself was more than enough, but he was sitting back in his usual relaxed position, making no apparent effort, until some corners were reached when the speed at which he controlled slides, winding the wheel from right to left and back again, showed that his superb reflexes and judgment were on top of their form.

The Moss/Jenkinson Mercedes races past spectators

Daimler

Cruising at maximum speed, we seemed to spend most of the time between Verona and Vicenza passing Austin-Healeys that could not have been doing much more than 115 m.p.h., and, with flashing lights, horn blowing and a wave of the hand, we went by as though they were touring. Approaching Padova Moss pointed behind and looked round to see a Ferrari gaining on us rapidly, and with a grimace of disgust at one another we realised it was Castellotti. The Mercédès-Benz was giving all it had, and Moss was driving hard but taking no risks, letting the car slide just so far on the corners and no more. Entering the main street of Padova at 150 m.p.h. we braked for the right-angle bend at the end, and suddenly I realised that Moss was beginning to work furiously on the steering wheel, for we were arriving at the corner much too fast and it seemed doubtful whether we could stop in time. I sat fascinated, watching Moss working away to keep control, and I was so intrigued to follow his every action and live every inch of the way with him, that I completely forgot to be scared. With the wheels almost on locking-point he kept the car straight to the last possible fraction of a second, making no attempt to get round the corner, for that would have meant a complete spin and then anything could happen. Just when it seemed we must go head-on into the straw bales Moss got the speed low enough to risk letting go the brakes and try taking the corner, and as the front of the car slid over the dry road we went bump into the bales with our left-hand front corner, bounced off into the middle of the road and, as the car was then pointing in the right direction, Moss selected bottom gear and opened out again.

All this time Castellotti was right behind us, and as we bounced off the bales he nipped by us, grinning over his shoulder. As we set off after him, I gave Moss a little handclap of appreciation for showing me just how a really great driver acts in a difficult situation.

“I was so intrigued to following Moss’ every action that I completely forgot to be scared”

Through Padova we followed the 4.4-litre Ferrari and on acceleration we could not hold it, but the Italian was driving like a maniac, sliding all the corners, using the pavements and the loose edges of the road. Round a particularly dodgy left-hand bend on the outskirts of the town I warned Moss and then watched Castellotti sorting out his Ferrari, the front wheels on full under-steer, with the inside one off the ground, and rubber pouring off the rear tyres, leaving great wide marks on the road. This was indeed motor-racing from the best possible position, and beside me was a quiet, calm young man who was following the Ferrari at a discreet distance, ready for any emergency. Out of the town we joined an incredibly fast stretch of road, straight for many miles, and we started alongside the Ferrari in bottom gear, but try as the Mercédès-Benz did the red car just drew away from us, and once more Moss and I exchanged very puzzled looks. By the time we had reached our maximum speed the Ferrari was over 200 yards ahead, but then it remained there, the gap being unaltered along the whole length of the straight. At the cut-off point at the end we gained considerably, both from the fact that we knew exactly when the following left-hand corner was approaching and also from slightly superior brakes. More full-throttle running saw us keeping the Ferrari in sight, and then as we approached a small town we saw Castellotti nip past another Ferrari, and we realised we were going to have to follow through the streets, until there was room to pass. It was number 714, Carini, so soon, and this encouraged Moss to run right round the outside of the Ferrari, on a right-hand curve, confident from my signals that the road would not suddenly turn left. This very brief delay had let Castellotti get away from us but he was not completely out of sight, and after waving to Peter Collins, who had broken down by the roadside before Rovigo, we went into that town at terrific speed. Straight across the square we went, where in practice we had had to go round the island; broadside we left the last right turn of the town, with the front wheels on full opposite lock and the throttle pedal hard down. Castellotti was in sight once more but out on the open roads he was driving so near the limit that on every corner he was using the gravel and rough stuff on the edges of the road. This sent up a huge cloud of dust, and we could never be sure whether or not we were going to enter it to find the Ferrari sideways across the road, or bouncing off the banks and trees, for this sort of hazard a scientific route navigating method could not cope with. Wisely, Moss eased back a little and the Ferrari got ahead of us sufficiently to let the dust clouds settle.

Along the new road by the side of the River Po we overtook Lance Macklin in his Austin-Healey, and he gave us a cheery wave, and then we went through Ferrara, under the railway bridge, over the traffic lights and down the main streets and out onto the road to Ravenna. All the way along there were signs of people having the most almighty incidents, black marks from locked wheels making the weirdest patterns on the road, and many times on corners we had signalled as dangerous or dodgy we came across cars in the touring categories lying battered and bent by the roadside, sure indication that our grading of the corner was not far wrong. To Ravenna the road winds a great deal and now I could admire the Moss artistry as he put in some very steady “nine-tenths” motoring, especially on open bends round which he could see and on those that he knew, and the way he would control the car with throttle and steering wheel long after all four tyres had reached the breakaway point was a sheer joy, and most difficult to do justice to with a mere pen and paper. Approaching the Ravenna control I took the route-card board from its holder, held it up for Moss to see, to indicate that we had to stop here to receive the official stamp, and then as we braked towards the “CONTROLLO” banner across the road, and the black and white chequered line on the road itself, amid waving flags and numerous officials, I held my right arm well out of the car to indicate to them which side we wanted the official with the rubber stamp to be. Holding the board on the side of the cockpit we crossed the control line, bang went the rubber stamp, and we were off without actually coming to rest. Just beyond the control were a row of pits and there was 723, Castellotti’s Ferrari, having some tyre changes, which was not surprising in view of the way he had been driving.

“All the way along there were signs of people having the most almighty incidents”

With a scream of “Castellotti!” Moss accelerated hard round the next corner and we twisted our way through the streets of Ravenna, nearly collecting an archway in the process, and then out on the fast winding road to Forli. Our time to Ravenna had been well above the old record but Castellotti had got there before us and we had no idea how Taruffi and the others behind us were doing. Now Moss continued the pace with renewed vigour and we went through Forli, waving to the garage that salvaged the SL we crashed in practice, down the fast winding road to Rimini, with another wave to the Alfa-Romeo service station that looked after the SLR that broke its engine. I couldn’t help thinking that we had certainly left our mark round the course during practice. Ever since leaving the start we had had the rising sun shining in our eyes and, now, with the continual effects of sideways “G” on my body, my poor stomach was beginning to suffer and, together with the heat from the gearbox by my left buttock, the engine fumes, and the nauseating brake-lining smells from the inboard-mounted brakes, it cried “enough” and what little breakfast I had eaten went overboard, together with my spectacles, for I made the fatal mistake of turning my head sideways at 150 m.p.h. with my goggles lowered. Fortunately, I had a spare pair, and there was no time to worry about a protesting stomach, for we were approaching Pesaro, where there was a sharp right corner.

Now the calm, blue Adriatic sea appeared on our left and we were on the long coastal straights, taking blind brows, and equally blind bridges at our full 170 m.p.h., and I chuckled to myself as I realised that Moss was not lifting his foot as he had threatened. We were beginning to pass earlier numbers very frequently now, among them some 2-litre Maseratis being driven terribly slowly, a couple of TR2 Triumphs running in convoy, and various saloons, with still numerous signs of the telling pace, a wrecked Giulietta on the right, a 1,100-c.c. Fiat on the left, a Ferrari coupé almost battered beyond recognition and a Renault that had been rolled up into a ball. Through Ancona the crowds were beautifully controlled, barriers keeping them back on the pavements, and we were able to use the full width of the road everywhere, and up the steep hill leaving the town we stormed past more touring-car competitors who had left in the small hours of the morning while we were still asleep. All this time there had been no signs of any of our close rivals. We had passed the last of the Austin-Healeys, driven by Abecassis, a long way back, and no Ferraris had appeared in our rear-view mirror.

Moss and Jenkinson pushing hard in their Mercedes

Daimler

It was a long way down to the next control point, at Pescara, and we settled down to cruising at our maximum speed, the car giving no impression at all of how fast it was travelling, until we overtook another competitor, who I knew must be doing 110 m.p.h., or when I looked sideways at the trees and hedges flashing past. It was now mid-morning and the sun was well above us but still shining down onto our faces and making the cockpit exceedingly hot, in spite of having all the air vents fully open. Through the dusty, dirty Adriatic villages we went and all the time I gave Moss the invaluable hand signals that were taking from him the mental strain of trying to remember the route, though he still will not admit to how much mental strain he suffered convincing himself that I was not making any mistakes in my 170 m.p.h. navigation. On one straight, lined with trees, we had marked down a hump in the road as being “flatout” only if the road was dry. It was, so I gave the appropriate signal and with 7,500 r.p.m. in fifth gear on the tachometer we took off, for we had made an error in our estimation of the severity of the hump. For a measurable amount of time the vibro-massage that you get sitting in a 300 SLR at that speed suddenly ceased, and there was time for us to look at each other with raised eyebrows before we landed again. Even had we been in the air for only one second we should have travelled some 200 feet through the air, and I estimated the “duration of flight” at something more than one second. The road was dead straight and the Mercédès-Benz made a perfect four-point landing and I thankfully praised the driver that he didn’t move the steering wheel a fraction of an inch, for that would have been our end.

“I saw a uniformed arm trying to switch off the ignition”

With the heat of the sun and the long straights we had been getting into a complacent stupor, but this little “moment” brought us back to reality and we were fully on the job when we approached Pescara. Over the level crossing we went, far faster than we had ever done in practice, and the car skated right across the road, with all four wheels sliding, and I was sure we were going to write-off some petrol pumps by the roadside, but somehow “the boy” got control again and we merely brushed some straw bales and then braked heavily to a stop for the second control stamp. Approaching this point I not only held the route-card for the driver to see, but also pointed to the fuel filler, for here we were due to make our first refuelling. However, I was too late, Moss was already pointing backwards at the tank himself to tell me the same thing. Just beyond the control line we saw engineer Werner holding a blue flag bearing the Mercédès-Benz star and as we stopped everything happened at once. Some 18 gallons of fuel went in from a gravity tank, just sufficient to get us to our main stop at Rome, the windscreen was cleaned for it was thick with dead flies, a hand gave me a slice of orange and a peeled banana, while another was holding a small sheet of paper, someone else was looking at the tyres and Moss still had the engine running. On the paper was written “Taruffi, Moss 15 seconds, Herrman, Kling, Fangio,” and their times; I had just yelled “second, 15 seconds behind Taruffi” when I saw a uniformed arm trying to switch off the ignition. I recognised an interfering police arm and gave it a thump, and as I did so, Moss crunched in bottom gear and we accelerated away as hard as we could go. What had seemed like an age was actually only 28 seconds!

Taruffi rounds hairpin bend in front of excited spectators

Motorsport Images

Over the bridge we went, sharp right and then up one of the side turnings of Pescara towards the station, where we were to turn right again. There was a blue Gordini just going round the corner and then I saw that we were overshooting and with locked wheels we slid straight on, bang into the straw bales. I just had time to hope there was nothing solid behind the wall of bales when the air was full of flying straw and we were on the pavement. Moss quickly selected bottom gear and without stopping he drove along the pavement, behind the bales, until he could bounce down off the kerb and continue on his way, passing the Gordini in the process. As we went up through the gears on the long straight out of Pescara, I kept an eye on the water temperature gauge, for that clonk certainly creased the front of the car, and may have damaged the radiator, or filled the intake with straw, but all seemed well, the temperature was still remaining constant. There followed three completely blind brows in quick succession and we took these at full speed, the effect being rather like a switchback at a fair, and then we wound and twisted our way along the barren valley between the rocky mountain sides, to Popoli, where a Bailey Bridge still serves to cross a river. Along this valley I saw the strange sight of about 50 robed monks, with shining bald pates, standing on a high mound and waving to us as we went by with a noise sufficient to wake the devil himself.

Up into the mountains we climbed, sliding round the hairpins with that beautiful Moss technique I described two months ago in Motor Sport, and then along the peculiar deserted plateau high up in the mountains we held our maximum speed for many kilometres, to be followed by a winding twisting road into Aquila, where up the main street the control was dealt with while still on the move. We certainly were not wasting any seconds anywhere and Moss was driving absolutely magnificently, right on the limit of adhesion all the time, and more often than not over the limit, driving in that awe-inspiring narrow margin that you enter just before you have a crash if you have not the Moss skill, or those few yards of momentary terror you have on ice just before you go in the ditch. This masterly handling was no fluke, he was doing it deliberately, his extra special senses and reflexes allowing him to go that much closer to the absolute limit than the average racing driver and way beyond the possibilities of normal mortals like you or me.

“Moss was driving absolutely magnificently, right on the limit of adhesion all the time, and more often than not over the limit”

On the way to Rome we hit a level crossing that had been just “bumpy” in the SL and smooth in the 220A7, the resultant thud threw us high out of our seats into the airstream, and with a crash we landed back again, nearly breaking our spines, but the Mercédès-Benz suspension absorbed it all without protest and there was no feeling that anything had “bottomed” unduly severely. This sort of thing had happened three or four times already, for our route noting was not infallible, and it seemed unbelievable that nothing broke on the car each time. Although we occasionally saw a train steaming along in the distance we never came across any closed level crossings, though if we had we had a remedy. In practice we had tried lifting the barrier, Italian gates being two long poles that lower across the road, and found that the slack on the operating cables was just sufficient to allow the car to be driven under the pole, much to the annoyance of the crossing-keeper. However, this did not arise and down into the Rome control we had a pretty clear run, being highly delighted to overtake Maglioli soon after Rieti, he suffering from an arm injury received in practice, and a car that was not going well. With a grin at each other we realised that one of our unseen rivals was now disposed of, but we still had Taruffi behind us on the road, and no doubt well ahead of us on time, for all this ground was local colour to him. Coming down off the mountains we had overtaken Musso driving a 2-litre Maserati and as we had calculated that we were unlikely ever to catch him, if we averaged 90 m.p.h. for the whole race, we realised we must be setting a fantastic record speed, but as Taruffi had been leading at Pescara, his average must be even higher.

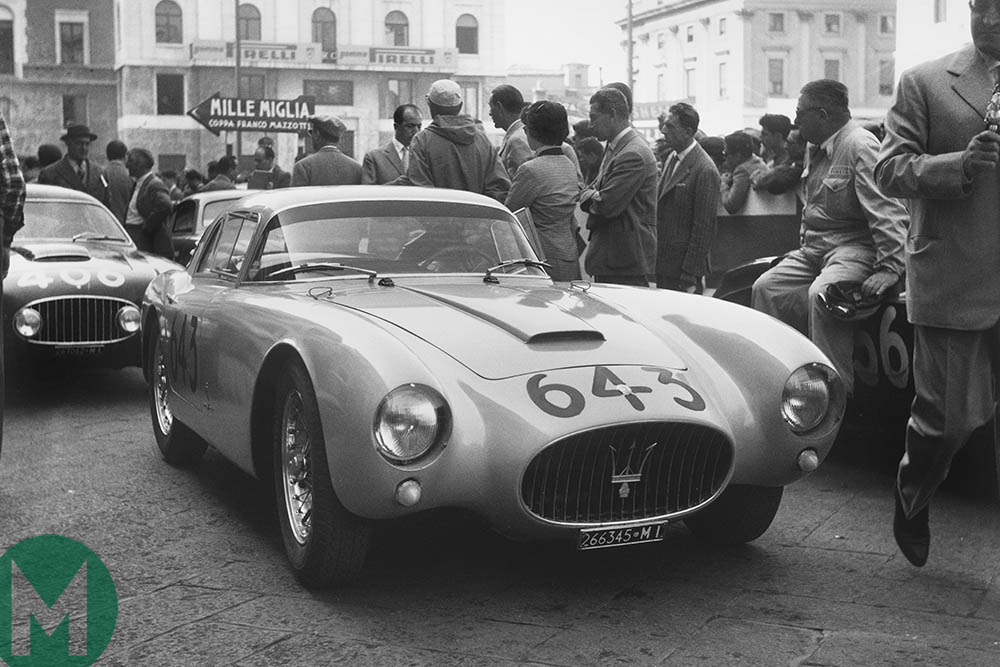

Sergio Sighinolfi’s Ferrari awaits scrutineering

Motorsport Images

The last six miles into the Rome control were an absolute nightmare; there were no corners that needed signals, and we would normally have done 150-160 m.p.h., but the crowds of spectators were so thick that we just could not see the road and the surface being bumpy Moss dared not drive much over 130 m.p.h. for there was barely room for two cars abreast. It seemed that the whole of Rome was out to watch the race, and all oblivious of the danger of a high-speed racing car. While I blew the horn and flashed the lights Moss swerved the car from side to side and this had the effect of making those on the very edge leap hastily backwards, thus giving us a little more room. The last mile into the control was better organised and I was able to show Moss the control card, point backwards at the fuel tank and also at the fibre disc wired to the steering column which had to be punched at this control. “Bang” went the stamp and we then drew into the Mercédès-Benz pit and switched off the engine; this was our first real stop since leaving Brescia nearly 3 1/2 hours ago, and our average speed to this point was 107 m.p.h., the average to Pescara having been 118 m.p.h., the mountain section causing it to drop from there to Rome.

As we stopped Moss leapt out to relieve himself, I felt the car rise up on the jacks and heard the rear hub nuts being beaten off, the windscreen was cleaned and a welcome shower of water sprinkled over me, for I was very hot, very tired, very dirty, oily and sweaty and must have looked a horrible sight to spectators. The fuel tank was being filled, someone handed me a drink of mineral water and an orange, and offered a tray of sandwiches and cakes, but I felt incapable of eating anything firmer than a slice of orange. A hand appeared in front of me holding a sheet of paper and I snatched it and read “Moss, Taruffi, Herrman, Kling, Fangio” and the times showed we had a lead of nearly two minutes. Bump went the car as it was dropped down off the jacks, and with a lithe bound Moss was into the driving seat again and as we took the hairpin after the control I managed to yell in his ear “First by more than one minute from Taruffi” and then the noise of the exhaust and wind prevented any further words. On the next bend we saw a silver Mercédès-Benz, number 701, well off the road among the trees and badly wrecked. We knew it was Kling and exchanged long faces with each other, wondering how badly hurt he was, but this had no effect on Moss and he now began to put everything he knew into his driving, on this most difficult section, while I had to concentrate hard in order to give him warnings and signals of the approaching road conditions, for this was indeed a difficult section for both of us.

Past Monterosi we waved to the “Agip” service station, where we had a sheep-killing incident in practice, and then we sped on our way through Vitterbo, sliding this way and that, leaving the ground on more occasions than I can remember, yet all the while feeling completely at ease for such is the confidence that Moss gave me, and round the corners I never ceased to marvel at the superb judgment with which he weighed up the maximum possible speed at which he could go, and just how far he could let the car slide without going into the ditch or hitting a wall or rock face. Now there was the continual hazard of passing slower cars, though it must be recorded that most of them gave way splendidly, keeping one eye on the mirror. Just after Aequapendente I made my first and only mistake in navigating, that it was not serious is why you are reading these words now; having just given warning of a very dodgy right-hand bend I received a shower of petrol down my neck and looking round to see what had happened we arrived at another similar corner, and I missed the signal. Fortunately Moss had recognised the corner, for he knew many parts of the course extremely well, and after seeing that the petrol was coming from the filler due to surge, I looked back to see an irate Moss face saying very rude things at me and shaking his fist, all the while cornering at a fantastic speed. How serious the fuel surge was I did not know, and as the exhaust pipes were on the side of the car I decided it would be all right and said nothing to Moss, as he appeared not to have received any of the spray.

Alberto Magi Diligenti’s Maserati before scrutineering

Motorsport Images

For the next 10 or 15 miles I received this gentle spray of cold fuel, cooling in the enormous heat of the cockpit, but a little worrying in case it got worse. Up the Radicofani Pass we stormed, and the way the car leapt and slithered about, would have really frightened me had I not already had a lot of experience of its capabilities and of the skill of Stirling Moss; as it was I sat there and revelled in the glorious feeling of really fast motoring. Over the top of the pass we swept past a saloon car competitor, into a downhill right-hand bend followed by a sharp left-hander. Now, previous to this Moss had been pointing to the front of the car and indicating that a brake was beginning to grab on occasions, and this was one of them. Without any warning the car spun and there was just time to think what a desolated part of Italy in which to crash, when I realised that we had almost stopped in our own length and were sliding gently into the ditch to land with it crunch that dented the tail. “This is all right,” I thought, “we can probably push it out of this one,” and I was about to start getting out when Moss selected bottom gear and we drove out — lucky indeed! Before we could point the car in the right direction we had to make two reverses and as we accelerated away down the mountainside I fiddled about putting the safety catch back on the reverse position of the gear-gate, while we poked our tongues out at each other in mutual derision.

At the Siena control we had no idea of whether we were still leading or not, but Moss was quite certain that Taruffi would have had to have worked extremely hard to catch him, for he had put all he knew into that last part of the course he told me afterwards. Never relaxing for an instant he continued to drive the most superb race of his career, twirling the steering wheel this way and that, controlling slides with a delicateness of throttle that was fairy-like, or alternatively provoking slides with the full power of the engine, in order to make the car change direction bodily, the now dirty, oily and battered collection of machinery that had left Brescia gleaming like new still answering superbly to his every demand, the engine always being taken to 7.500 r.p.m. in the gears, and on one occasion to 8,200 r.p.m., the excitement of that particular instant not allowing time for a gear change or an easing of the throttle, for the way Moss steered the car from the sharp corners with the back wheels was sheer joy to experience.

“The car spun and there was just time to think what a desolated part of Italy in which to crash”

On the winding road from Siena to Florence physical strain began to tell on me, for with no steering wheel to give me a feel of what the car was going to do, my body was being continually subjected to terrific centrifugal forces as he car changed direction. The heat, fumes and noise were becoming almost unbearable, but I gave myself renewed energy by looking at Stirling Moss who was sitting beside me, completely relaxed, working away at the steering as if we had only just left Brescia, instead of having been driving for nearly 700 miles under a blazing sun. Had I not known the route I would have happily got out there and then, having enjoyed every mile, but ahead lay some interesting roads over which we had practised hard, and the anticipation of watching Moss really try over these stretches, with the roads closed to other traffic, made me forget all about the physical discomforts. I was reminded a little of the conditions when we approached one corner and some women got up and fled with looks of terror on their faces, for the battered Mercédès-Benz, dirty and oil-stained and making as much noise as a Grand Prix car, with two sweaty, dirty, oil-stained figures behind the windscreen, must have looked terrifying to peaceful bystanders, as it entered the corner in a full four-wheel slide.

The approaches of Florence were almost back-breaking as we bounced and leapt over the badly maintained roads, and across the tramlines, and my heart went out to the driver of an orange Porsche who was hugging the crown of the steeply cambered road. He must have been shaken as we shot past with the left-hand wheels right down in the gutter. Down a steep hill in second gear, we went, into third at peak revs. and I thought “it’s a brave man who can unleash nearly 300 b.h.p. down a hill this steep and then change it into a higher gear.” At speeds up to 120-130 m.p.h. we went through the streets of Florence over the great river bridge, broadside across a square, across more tramlines and into the control point. Moss had really got the bit between his teeth, nothing was going to stop him winning this race, I felt; he had a rather special look of concentration on his face and I knew that one of his greatest ambitions was to do the section Florence-Bologna in under one hour. This road crosses the heart of the Apennines, by way of the Futa Pass and the Raticosa Pass, and though only just over 60 miles in length it is like a Prescott Hill-Climb all the way. As we got the route-card stamped, again without coming to rest, I grabbed the sheet of paper from the Mercédès-Benz man at the control, but before I could read more than that we were still leading, it was torn from my grasp as we accelerated away among the officials. I indicated that we were still leading the race, and by the way Moss left Florence, as though at the start of a Grand Prix, I knew he was out to crack one hour to Bologna, especially as he also looked at his wrist-watch as we left the control. “This is going to be fantastic,” I thought, as we screamed up the hills out of Florence, “he is really going to do some nine-tenths plus motoring” and I took a firm grip of the “struggling bar” between giving him direction signals, keeping the left side of my body as far out way as possible, for he was going to need all the room possible for his whirling arms and for stirring the gear-lever about.

Up into the mountains we screamed, occasionally passing other cars, such as 1900 Alfa-Romeos, 1,100 Fiats and some small sports cars. Little did we know that we had the race in our pocket, for Taruffi had retired by this time with a broken oil pump and Fangio was stopped in Florence repairing an injection pipe, but though we had overtaken him on the road, we had not seen him, as the car had been hidden by mechanics and officials. All the time l had found it very difficult to take my eyes off the road. I could have easily looked around me, for there was time, but somehow the whole while that Moss was really dicing I felt a hypnotic sensation forcing me to live every inch of the way with him. It was probably this factor that prevented me ever being frightened for nothing arrived unexpectedly. I was keeping up with him mentally all the way, which I had to do if I wasn’t to miss any of our route marking, though physically I had fallen way behind him and I marvelled that anyone could drive so furiously for such a long time, for now it was well into Sunday afternoon. At the top of the Futa Pass there were enormous crowds all waving excitedly and on numerous occasions Moss nearly lost the car completely as we hit patches of melted tar, coated with oil and rubber from all the other competitors in front of us, and for nearly a mile he had to ease off and drive at a bare eight-tenths, the road was so tricky. Just over the top of the Futa we saw a Mercédès-Benz by the roadside amid a crowd of people, it was 704, young Hans Herrmann, and though we could not see him, we waved. The car looked undamaged so we assumed he was all right.

The Mercedes races through almost countless Italian towns

Daimler

Now we simply had to get to Brescia first, I thought, we mustn’t let Taruffi beat us, still having no idea that he had retired. On we went, up and over the Raticosa Pass, plunging down the other side, in one long series of slides that to me felt completely uncontrolled but to Moss were obviously intentional. However, there was one particular one which was not intentional and by sheer good fortune the stone parapet on the outside of the corner stepped back just in time, and caused us to make rude faces at each other. On a wall someone had painted “Viva Perdisa, viva Maserati” and as we went past in a long controlled slide, we spontaneously both gave it the victory sign, and had a quiet chuckle between ourselves, in the cramped and confined space of our travelling hothouse and bath of filth and perspiration. On another part of the Raticosa amid great crowds of people we saw an enormous fat man in the road, leaping up and down with delight: it was the happy body-builder of the Maserati racing department, a good friend of Stirling’s, and we waved back to him.

Down off the mountains we raced, into the broiling heat of the afternoon, into Bologna along the dusty tram-lined road, with hordes of spectators on both sides, but here beautifully controlled, so that we went into Bologna at close to 150 m.p.h. and down to the control point, Moss doing a superb bit of braking judgment even at this late stage of the race, and in spite of brakes that were beginning to show signs of the terrific thrashing they had been receiving. Here we had the steering column disc punched again and the card stamped, and with another Grand Prix start we were away through the streets of Bologna so quickly that I didn’t get the vital news sheet from our depot. Now we had no idea of where we lay in the race, or what had happened to our rivals, but we knew we had crossed the mountains in 1 hr. 1 min., and were so far ahead of Marzotto’s record that it seemed impossible. The hard part was now over, but Moss did not relax, for it had now occurred to him that it was possible to get back to Brescia in the round 10 hours, which would make the race average 100 .m.p.h. Up the long fast straights through Modena, Reggio Emilia and Parma we went, not wasting a second anywhere, cruising at a continuous 170 m.p.h. cutting off only where I indicated corners, or bumpy hill-brows. Looking up I suddenly realised that we were overtaking an aeroplane, and then I knew I was living in the realms of fantasy, and when we caught and passed a second one my brain began to boggle at the sustained speed. They were flying at about 300 feet filming our progress and it must have looked most impressive, especially as we dropped back by going round the Fidenza by-pass, only to catch up again on the main road. This really was pure speed, the car was going perfectly and reaching 7,600 r.p.m. in fifth gear in places, which was as honest a 170 m.p.h. plus. as I’d care to argue about.

Moss did not relax, for it had now occurred to him that it was possible to get back to Brescia in the round 10 hours, which would make the race average 100 .m.p.h.

Going into Piacenza where the road doubles back towards Mantova we passed a 2cv Citroën bowling along merrily, having left Brescia the night before, and then we saw a 2-litre Maserati ahead which shook us perceptibly for we thought we had passed them all long ago. It was number 621, Francesco Giardini, and appreciating just how fast he must have driven to reach this point before us, we gave him a salutary wave as we roared past, leaving Piacenza behind us. More important was the fact we were leaving the sun behind us, for nice though it was to have dry roads to race on, the blazing sun had made visibility for both of us tiring. Through Cremona we went without relaxing and now we were on the last leg of the course, there being a special prize and the Nuvolari Cup for the fastest speed from Cremona to Brescia. Although the road lay straight for most of the way, there were more than six villages to traverse, as well as the final route card stamp to get in the town of Mantova. In one village, less than 50 miles from the finish, we had an enormous slide on some melted tar and for a moment I thought we would hit a concrete wall, but with that absurdly calm manner of his, Moss tweaked the wheel this way and that, and caught the car just in time, and with his foot hard down we went on our way as if nothing had happened. The final miles into Brescia were sheer joy, the engine was singing round on full power, and after we had passed our final direction indication I put my roller-map away and thought “If it blows to pieces now, we can carry it the rest of the way.” The last corner into the finishing area was taken in a long slide with the power and noise full on and we crossed the finishing line at well over 100 m.p.h, still not knowing that we had made motor-racing history, but happy and contented at having completed the whole race and done our best.

Moss and Jenkinson celebrate taking victory

Daimler

From the finishing line we drove round to the official garage, where the car had to be parked and Stirling asked “Do you think we’ve won?” to which I replied, “We must wait for Taruffi to arrive, and we don’t know when Fangio got in” — at the garage it was finally impressed upon us that Taruffi was out, Fangio was behind us and we had won. Yes, won the Mille Miglia, achieved the impossible, broken all the records, ruined all the Mille Miglia legends, made history. We clasped each other in delirious joy, and would have wept, but we were too overcome and still finding it hard to believe that we had won. Then we were swept away amid a horde of police and officials, and the ensuing crush amid the wildly enthusiastic crowds was harder to bear than the whole of the 1,000-mile grind we had just completed.

Our total time for the course was 10 hr. 07 min. 48 sec., an average of more than 157 k.p.h. (nearly 98 m.p.h.) and our average for the miles from Cremona to Brescia had been 123 m.p.h. As we were driven back to our hotel, tired, filthy, oily and covered in dust and dirt, we grinned happily at each other’s black face and Stirling said “I’m so happy that we’ve proved that a Britisher can win the Mille Miglia, and that the legend ‘he who leads at Rome never leads at Brescia’ is untrue — also, I feel we have made up for the two cars we wrote off in practice,” then he gave a chuckle and said “We’ve rather made a mess of the record, haven’t we — sort of spoilt it for anyone else, for there probably won’t be another completely dry Mille Miglia for twenty years.”

It was with a justified feeling of elation that I lay in a hot bath, for I had had the unique experience of being with Stirling Moss throughout his epic drive, sitting beside him while he worked as I have never seen anyone work before in my life, and harder and longer than I ever thought it possible for a human being to do. It was indeed a unique experience, the greatest experience in the whole of the 22 years during which I have been interested in motor-racing, an experience that was beyond my wildest imagination, with a result that even now I find it extremely hard to believe.

After previous Mille Miglias I have said “he who wins the Mille Miglia is some driver, and the car he uses is some sports car.” I now say it again with the certain knowledge that I know what I’m talking and writing about this time. — D. S. J.

No comments:

Post a Comment